Cross Boundary

【S-4】Crossboundary of Lighting design

With today’s various mounting social challenges, we are witnessing big shifts in architectural and urban design methodologies, and untraditional approaches being experimented with. Within this context of a changing society, by following the presentations of eight lighting designers about their works, we examine “what it means to cross boundaries” for lighting design and designers.

The moderator, Shiho Nagamachi, opened with a short introduction to the event’s theme: “Cross Boundary.” When envisioning a lighting design that goes beyond current limits, lighting designers are looking to change the profession of lighting and explore its future, in other words: Innovation and Expansion. The eight invited speakers all have experience in exceeding these boundaries in their work, and each had four minutes to present how they approach the challenge of innovation and the expansion of their field.

Satoshi Uchihara was the first to present. He noted how the uniformity of lighting design in redevelopment and other projects in urban centers has started to change, referring to growing opportunities to participate for lighting designers as it is for architects and interior designers. He also discussed the importance of ensuring areas of “moderate darkness” in our city-center nightscapes, considering the lighting balance. When looking at this balance, visualizing whether to divide equally or share is essential. As lighting designers utilize their skills and expand their field of design, it will become increasingly necessary to design both light that adds and detracts based on the idea of “sharing.”

Masanobu Takeishi spoke next, citing a hotel renovation project he was involved in. Consulting with the hotel staff to, for example, place plants like a bar in the area in front of the restaurant creating a waiting space, suggesting for lighting to be installed there to create shadows on the ceiling, or for the walls to be painted, expanding the proposal scope by using the original lighting design discussions. Even just changing parking lighting colors to warm white can cause visitors to sense a difference. He further elaborates on his philosophy towards lighting: “The power of lighting is not only that it is easily understood when perceived, but also that it can be experienced through the senses. I think this is important.”

Tsukasa Masuda addressed the audience next, introducing a case where he was approached by a Fukuoka resident to remodel their home into a high-end but casual retail space. It was the first time that he took charge of all aspects from lighting to interior design, furniture production, and construction management, as per the client’s request. He explained how he especially took care in considering the flow of time for the customers and store owner when designing. Nagamachi asked how different this project was from his usual work that does not cross borders, to which Masuda responded by highlighting how different it is to think of lighting design from drawings to space, with architectural planning, as compared to his normal workflow.

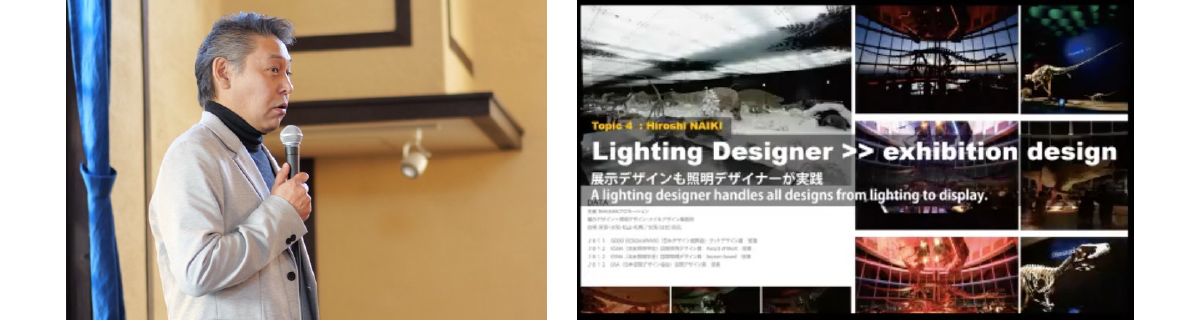

The fourth speaker was Hiroshi Naiki, delving into how his work has transcended lighting design to the field of exhibition design. When designing an exhibition space that also focuses on lighting, how interesting could the lighting effects and the charm of the exhibits become if everything were to be coordinated by yourself? He states, “From a young age, before thinking as a lighting designer, I always thought as a designer first, considering what kind of spatial expressions I could produce. This has enabled me to freely choose the components, including the materials, needed for exhibitions. To reach beyond the limits is to ask, ‘How far can we go?’ building on each experience.”

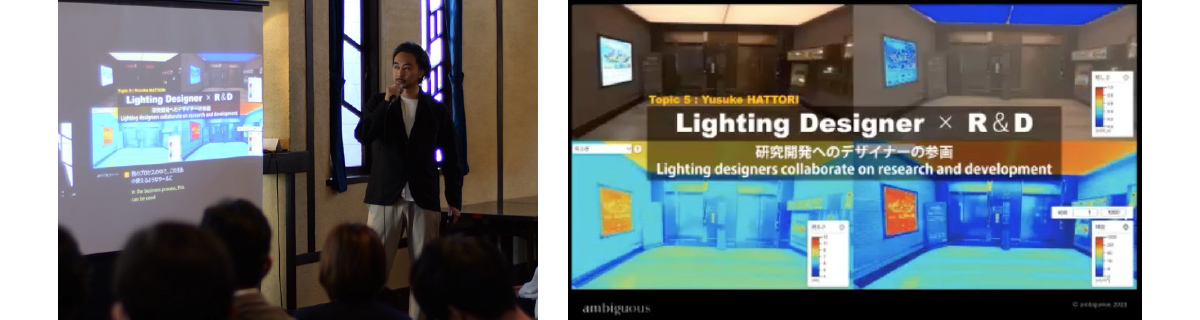

The fifth speaker, Yusuke Hattori, is based in Singapore. He established the company “ambiguous,” where they actively engage in crossing boundaries. An example of this is their collaboration with research organizations to develop tools to help utilize luminance distribution and brightness perception in lighting design, which cannot be done solely with illuminance. Hattori goes on to say, “Japan’s research on luminance and brightness perception is the world’s most advanced, so we should take Japanese luminance design as an example and put it into practice.” He also touched on how, from the outside, Japanese people seem to do things in a uniquely ambiguous way and, realizing the importance of ambiguity himself, expressed his resolve to continue with activities not restricted to any one genre.

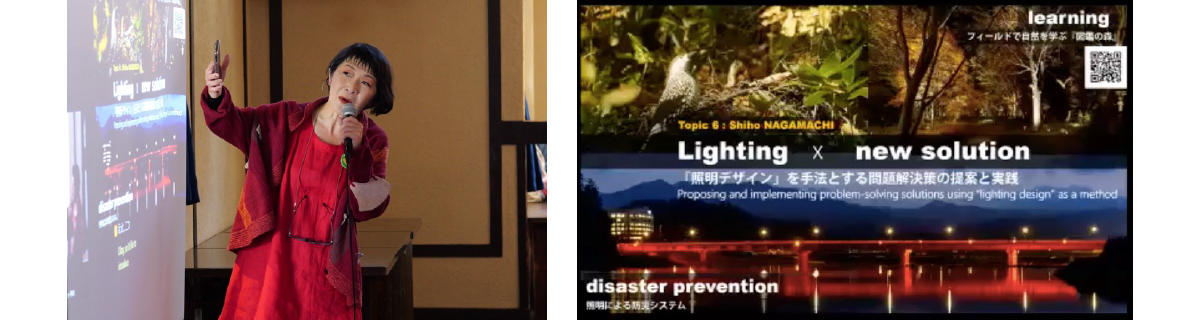

The sixth speaker was moderator Shiho Nagamachi. She started by explaining why the two projects in Hokkaido and Kyushu were out of the ordinary: “Neither project was planned from the start. This happens very often in our work, and projects are usually proposed by myself (and my office).” Opportunities arise when consulting with people from the government and communities, and new projects come about where there were no plans before. From there, we investigate if lighting in itself can be used as a solution, or in other words, using standard architectural lighting skills to address a different issue. She expressed that this is the way she actively crosses boundaries.

The seventh to present was Hisaki Kato. He founded a design unit together with a mechanical design engineer and an aerospace engineer, producing “Brightone,” a work created with the concept of “expanding music,” analyzing sound played in real-time and matching light to the sound. Kato explains, “We did this because it is interesting when the sounds you play as the musician are visualized as light right there to, if only slightly, create a different performance than usual, or inspire the performer’s musicality.” The three enthusiastically played around with this project and the resulting interest it generated led to exchanges and connections with various other industries. By viewing the lighting design industry from a wide angle, they feel they have been able to gain new insights.

The eighth speaker was Taro Nakatani. With not many videographers specializing in architectural lighting, Nakatani decided to go from lighting designer to videographer, motivated to capture the designer’s perspective in his work. Nakatani spoke about how he strives to portray a space’s three-dimensionality and the designer’s intent, aiming to create design-phase 3D walk-through images that are in sync with real-life images captured after construction is completed. In the future, the use of drones will most likely play a part in lighting design, including equipment programming and video production, and he hopes this will become a bridge to allow lighting designers to collaborate in newer ways.

Uchihara, Nakatani, and moderator Nagamachi gave their summaries to close the session. Nakatani said, “I believe the future of lighting design is bright if we continue to expand in ways that make the most of each individual and extend beyond the field.” Uchihara commented, “It is fascinating to see my values, the results of my activities, and many other things making their way back to me as completely different experiences.” Nagamachi concluded the seminar by sharing her expectations for the potential of lighting: “Just as we use the power of lighting every day to resolve various issues, there are still many things that can benefit from lighting’s capabilities.”