Asian Network

【S-2】Asian Crossroad/Let’s be inspired together!

This seminar aims to enhance the field of lighting design and facilitate cultural understanding by creating an opportunity for networking and delving into different cultures. Lighting designers from six Asian countries discussed their various lighting cultures and values, fostering a global exchange of ideas and experiences of working in the profession. Acting as moderator, Yusuke Hattori of ambiguous, who practices in Singapore and Tokyo, opened with slides allowing the panelists to present the culture and current situation of the lighting design industry in the country where they are from or work.

Each panelist introduced the culture and the state of the lighting design industry in their related country. Hattori started by discussing Singapore, where he has worked and resided for over 15 years. Singapore is a small Southeast Asian island known for its cultural and religious diversity and tropical climate. He explained that while it is renowned for its large financial market, it is also infamous as the most light-polluted country in the world, and he feels as a lighting designer, this issue must be dealt with as well. Next, he handed the microphone to Shigeki Fujii.

Fujii is the co-founder and director of Nipek, which has offices in Singapore and Hokkaido, where he currently lives. He explains: “Traditionally, Japanese residences utilized indirect light, which became a quality of light characteristic of the timber houses of the time. In his book In Praise of Shadows, Junichiro Tanizaki appreciates the beauty and shadow that lies within the harmony of light and shadow. Then came the great postwar economic boom through to the early 1990s, clearly transforming Japanese values with it, causing bright lighting to now be considered a good thing. Yet, COVID-19 reminded us once again that humans form part of nature. Environmental consideration and human health have started being prioritized over the economy, causing lighting design to go through some drastic changes as well.” Fujii is enthusiastic about advocating for and spreading the concept of “letting night be night,” restoring the natural light of the night or the natural night.

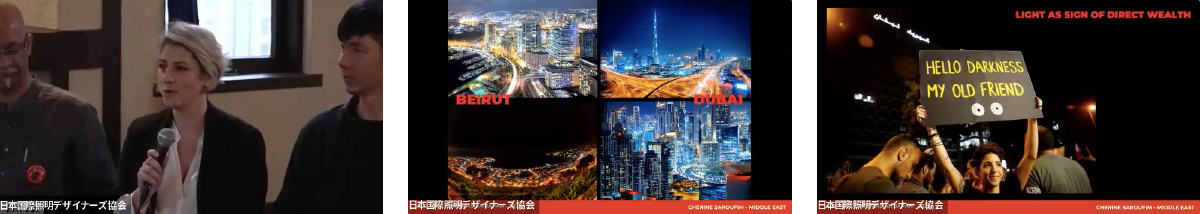

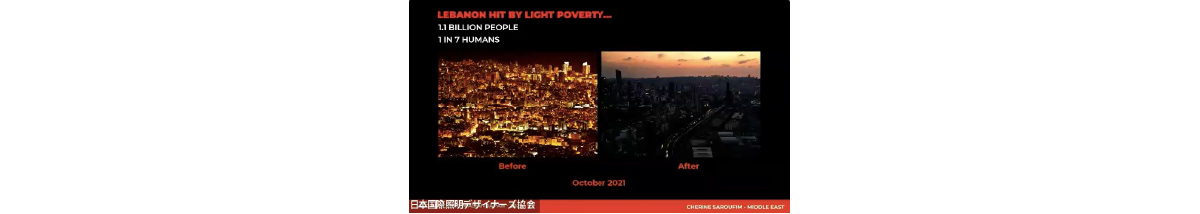

The third panelist, Cherine Saroufim, is based in Lebanon but is also active in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, and Syria. She started by explaining how Lebanon has been hit by several misfortunes in the last four years and now suffers from what is called “light poverty,” where even though it seems like a developing city, it has a shortage of artificial lighting. Despite the global acknowledgment that light is a resource as equally fundamental as food, shelter, and clean water, the very over-illumination of urban areas itself is becoming the problem of our generation. People tend to believe that the more lights within cities, the better, but particularly in Lebanon, where electricity is now very limited, only the more affluent people who can afford to possess generators have access to electricity, meaning more light has automatically come to mean more wealth. This has been noted across all the areas where Cherine works, and she is currently tackling this challenge hoping to someday find a resolution.

Next in line was Linus Lopez, who is based in Delhi and has various projects in different regions of India and a few other countries. He began his career 32 years ago as an electrical engineer of which 23 years have been in the lighting design industry. Looking back on his journey to becoming a lighting designer, he mentions that his purpose was “to take lighting design into the consciousness of people to let them understand the value it brings.” Although there are at present two lighting design societies in India — IALD India and the recently formed Lighting Designers Association of India, no courses in lighting design are available. Hence, to expand India’s lighting design profession, there is a need to first learn lighting design outside of India. Lopez states that it is only when people come back with an understanding of what lighting design can do, that they can improve the situation India is in.

Taking the mike next was Jinkie De Jesus who opened by expressing her hopes that the event would encourage her to experience the wonderful city of Tokyo at night and gain some insight into the Philippine lighting design scene. With beautiful beaches, waterfalls, and mountains, the Philippines is considered one of the world’s top travel destinations. On the other hand, because of often-occurring natural disasters such as typhoons, earthquakes, and floods, outdoor lighting fixtures have to be designed to withstand severe weather conditions. The Philippines’ hot and humid climate is increasingly getting worse as a result of climate change, with more people preferring to exercise and engage in social activities at night, giving even more value to the role of the lighting designer. The Philippines is experiencing growth and demand for showcase and facade lighting is increasing, while brighter lighting designs are favored for infrastructure like airports and large roads. Lighting design in the Philippines is currently faced with the problem of only being introduced in the high-end sector.

The last in line to introduce himself was Uno Lai: “I was born in Taiwan, went to New York to study, then came back to Asia around 2005 and started my own company. Ever since then, I found myself as not only a designer but more a businessman.” He provided an overview of the current appearance of the cities he has worked in, including China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. While citing examples from Shanghai and Chengdu, he elaborated: “In China, lighting is used not only to celebrate prosperity but also as a symbol of advancing economy, and in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, media facades displaying light shows, holiday messages, and text messages are widely used. Then you have Taiwan, which has developed its own culture, where the lighting is quite subtle and elegant and not as bright when compared to mainland China.”

The panelists’ self-introduction finished followed by the next topic, “Vocabulary or expression related to light or lighting.” Language has a cultural and historical backdrop that impacts how people think and act. Hattori explained that by understanding these words, a deeper understanding of the represented countries could be reached. He started with the example of the Japanese word “komorebi,” which has no direct English translation, and asked whether there are similar words in any of the other countries.

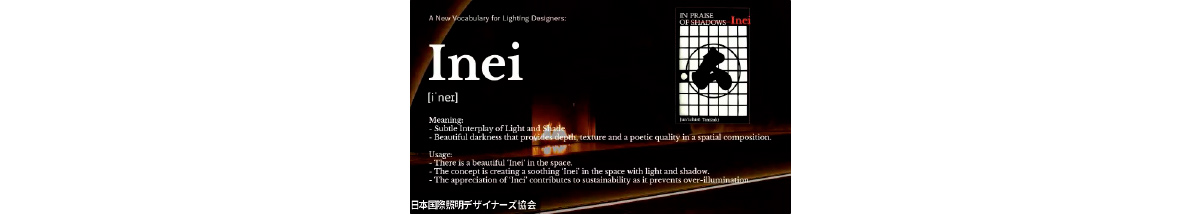

Responding to the question, Fujii introduced “Inei.” He explains that the Japanese word “Inei” does not only mean “shadow,” but rather the interplay of light and shadow. By proposing to the client, “We will design this space with beautiful ‘Inei’,” what essentially means “shadow” can be communicated with the nuance of designing a delicate play of light and shadow. He remarks that this word has a beautiful and poetic quality to it.

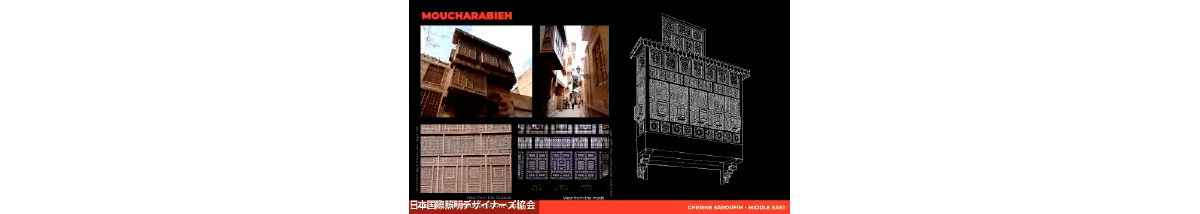

Cherine Saroufim noted that while there is no exact term referring to light and shadow in Lebanese culture like “Inei” does, they do have an architectural element that represents this phenomenon called a “Moucharabieh,” which is a kind of projecting window. The wooden lattice windows block out harsh daylight and also release the moisture it absorbs at night when the sunlight heats it during the day, thereby allowing cooler air into the room. She further mentions that one can choose where and how much light, ventilation, and privacy one would want, and that at night it acts as a lantern.

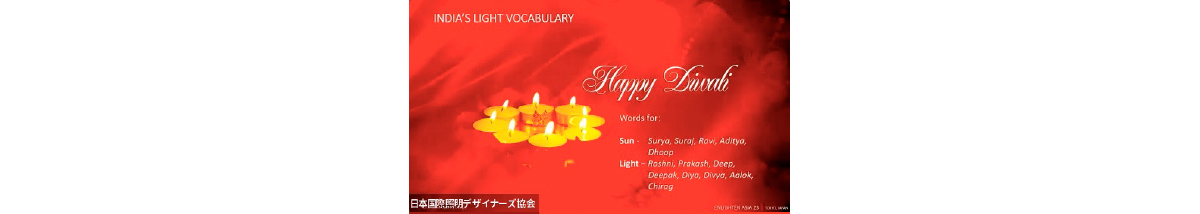

Linus Lopez explained that though India does not have many terms describing lighting effects, it has numerous words related to light itself. For example, the sun has phonetically similar names like “Surya” and “Suraj;” light has three words with totally different syllabic sounds namely: “Roshni,” “Prakash,” and “Deep.” There are also a lot of words for shadow, but they have negative associations, like in the case of darkness. He discusses how lighting designers have to reconsider how we define darkness and what good shadow can bring us.

Jinkie De Jesus described how the Philippine language is a mixture of Spanish, Bahasa, and Malay words. The word “maaliwalas,” meaning “bright and airy” in English, is used by clients when they want uniformly lit, bright, spaces with few shadows. “Sinag” refers to the rays of the sun, but can also mean glare. “Kislap” means sparkling while “Kutitap” refers to twinkling. “Pundido” comes from a Spanish word and only refers to when a light bulb goes out or the light is broken.

Uno Lai recalls that he had always been fond of the moon, even before becoming a lighting designer. In Chinese culture, the world can be divided into yin and yang. Yang is the sun and indicates positivity, while yin indicates darkness. Elaborating, he states that the only thing that can be “yang” in that darkness is the moon and that the moon has been referenced in countless events and poems celebrating the night. He notes that we have different scientific names for each phase of the moon and that in his experience, using the moon conceptually always succeeds when presenting it as an idea to clients. Although the moon is simply reflecting the sun’s light, it becomes a light source at night, and the presence of the bright moon makes the existence of darkness stand out. When we consider that lighting designers are not only creating light but also shadow to emphasize light, that is precisely what the moon does. Lai goes on to say that this was a great personal discovery and that the effects of the moon are not only fascinating to him but also very helpful when it comes to his work.

The next discussion was divided into two categories of problems that lighting designers face. First, the fundamental social issues unique to each country, and second, common issues that everyone faces, irrespective of country. Hattori invited Linus Lopez to explain the challenges that India is facing.

Linus Lopez comments, “As came up earlier in the conversation, the association between light and wealth is something that concerns me not just as a lighting designer, but also as one of the 7 billion inhabitants of this planet.” Clients have come to see light as a luxury instead of a need and it is becoming a way to show wealth and newfound positions of power. There is also concern that even though utilizing LEDs has lowered lighting’s percentage of the total global energy consumption, the amount of energy we use when considering the scale of a country like India continues to be an important issue. At the same time, sustainability in the selection of materials is another key consideration. Indian society grew with the concept of the waste recyclers called “kabadiwala,” and only now that they have been shunned from society, we have finally realized that a circular economy is the only way to reach sustainability. It is essential to advocate for the introduction of this circular economy into the Indian manufacturing processes.

Uno Lai agreed, commenting that “China also expends a lot of energy, and it is a common challenge.”

Cherine Saroufim discussed how Lebanon’s many unfortunate events have resulted in the loss of light. People who have lived with light all their lives do not know how to live in darkness, and many have fallen into a depressive state. A large number of non-governmental organizations help provide lighting by substituting existing lighting with solar-powered fixtures or by utilizing the generators installed in buildings. Furthermore, private institutions and individuals have maintained and supplied infrastructure since the government cannot be relied on. Yet, when we take a look at the current environmental situation, air pollution has seen a drastic increase. She further explained their present circumstances, saying that all the private generators and solar power have added to energy usage even more than before, reducing sustainability.

Jinkie De Jesus discussed how the Philippines’ lighting problems are closely related to the many issues facing society such as governmental instability, lack of peace and order, and high crime rates. The harm from light pollution is not seen as a priority, and guidelines on light pollution are limited to those implemented by private and wealthy developers, creating a large difference in the night scenery between these privately owned estates and the areas outside of them. She also added that other than the poor quality of lighting installation workmanship, the two biggest problems faced are vandalism and theft, which she attributed to the foundational problem of low educational standards in the Philippines.

Linus Lopez could relate to this issue and expressed the importance of using this as a learning experience.

The discussion moves on to the universal problems faced by lighting designers. Working in China, Uno Lai describes how he faces design and business challenges. Chinese clients have increasingly unreasonable expectations and excessive demands when it comes to the design side of lighting, and on the business side, it is becoming progressively challenging to hire qualified designers who really want to work for a pure lighting design company.

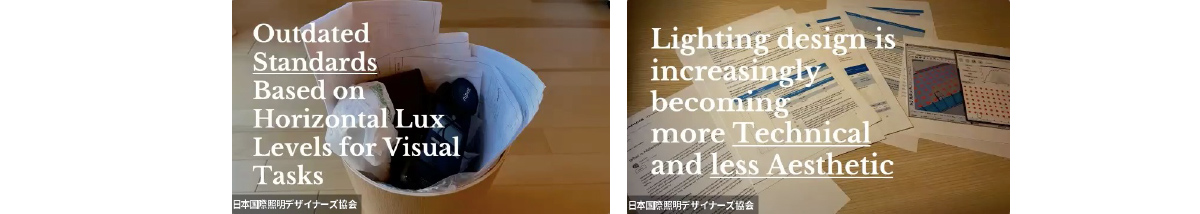

Fujii mentioned that horizontal lux level standards for visual work are a problem that lighting designers should not forget. The issue of lux levels for visual work might not be as prominent in Japan, even in projects where lighting designers are involved, but in Singapore and other countries, this topic always pops up. He admits that even though this is an extremely pressing problem, he does not know the way to solve it. The other problem that he pointed out is that lighting design, which should be something that cannot be measured, is now assessed with numbers and metrics.

Indicators for lux level uniformity and lighting power density began to be used about 10 years ago. More recently, various other metrics have emerged, such as illuminance, used to prevent light pollution, and wavelength regulations, which take into consideration light’s impact on circadian rhythms. While the use of these measurements is necessary to optimize lighting design for sustainability and human health, they tend to restrict what lighting designers can do. He underlines that though all lighting designers should be conscious of these indicators and actively use them, they must not forget that they can bring more value than merely just meeting the numbers.

Hattori shared Fujii’s sentiment, elaborating: “We still need to deal with sustainability at the base level, and then we have to go beyond all of that to work on real design.”

To close with, the participants shared their impressions of Japanese lighting design and how it differs from their countries.

Fujii presented a slide showing Tokyo Station noting that “this is a beautiful place, it feels pleasant, safe and clean, and is nicely dim. So I think Japanese lighting design has a lot to say. Maybe collecting photos and lux levels data of places like these could help other parts of the world accept more darkness.”

Cherine Saroufim was visiting Japan for the first time and found herself surprised by the gap between the Japan she saw on the Internet and Japan in reality. She commented, “The city I walked through yesterday was pretty dim, and I love it. It makes me feel like I belong in this city where people can live without having so much light.”

Linus Lopez shared that Junichiro Tanizaki’s philosophy of, “there is no beauty without shadow,” changed the way he thought about lighting design.

Jinkie De Jesus described the similarities between Japan and the Philippines, such as the capiz windows, which somewhat resemble Japanese shoji, and the bright lighting preferred in the department and retail stores. She hopes that the Philippines can develop its own lighting identity in the same way that Japan has its characteristic lighting design.

Uno Lai explained that when we think about lighting design, everything involves layers, contrast, and hierarchy, and Japan does this very well. Pointing at the two slides, he remarks: “Not all the buildings are always lit, and not every building wants to stand out and be the brightest.” He ended the session by explaining that it was Japanese lighting design taught him about this hierarchy.